Afghanistan: Written again in British blood

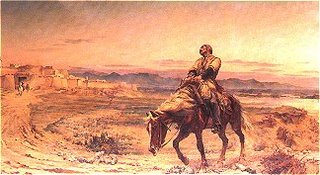

Remnants of an Army by Lady Elizabeth Butler. Depicting Dr William Brydon, an assistant surgeon on the Bengal Army arriving at the gates of Jellabad on his exhausted and dying horse. He was thought to be the sole survivor of some 16,000 strong army and followers from Kabul, which was forced to retreat the 90 miles over snow covered passes to Jellabad during the first Afghan war. A few others eventually struggled through to the fort.

Remnants of an Army by Lady Elizabeth Butler. Depicting Dr William Brydon, an assistant surgeon on the Bengal Army arriving at the gates of Jellabad on his exhausted and dying horse. He was thought to be the sole survivor of some 16,000 strong army and followers from Kabul, which was forced to retreat the 90 miles over snow covered passes to Jellabad during the first Afghan war. A few others eventually struggled through to the fort.Times Online

On January 13, 1842, a lookout on the walls of Jalalabad fort spotted a lone horseman, weaving towards the British outpost, on a dying horse. Part of the rider's skull had been removed by an Afghan sword; his life had been saved only by the copy of Blackwood's Magazine stuffed into his hat to stave off the intense cold, which had blunted the blow. This was Dr William Brydon, the sole survivor of a 16,000-strong force that had left Kabul a week earlier, only to be massacred in the mountain passes by rebellious Afghan tribesmen.

Dr Brydon's dramatic escape was celebrated in Victorian print, verse and paint. Lady Elizabeth Butler painted a tableau of the injured surgeon staggering towards salvation. The retreat from Kabul was the single worst disaster to befall the British Empire up to that point, but the adept Victorian propaganda machine managed to extract a tale of heroism from the calamity.

According to oral tradition in Afghanistan, however, Dr Brydon was not a heroic survivor but a hostage to history: the tribesmen deliberately let him escape so that he might return to his own people and tell of the ferocity and bravery of the Afghan tribes. Battered Dr Brydon was spared as a warning to the British: leave Afghanistan, and never come back.

The British paid no attention, of course. Two more Anglo-Afghan wars followed. Now that we are effectively involved in a fourth, with 3,300 British troops fighting to hold down the province of Helmand, the ghost of Dr Brydon rides again.

On Wednesday Taleban fighters in Helmand killed another British soldier, the sixth to die there in the last three weeks. The response of the deputy camp commander of Camp Bastion was both sad and wise: "We thought we would play the 'British not American' card. But it hasn't been so easy. There's a lot of history here."

There is indeed a lot of history in Afghanistan. In Britain we also have a lot of history, but we treat it differently. In Afghanistan, history is not simply a story of past events, but a living, continual experience, to be carefully tended, its meanings, lessons and resentments preserved and nurtured.

What happened in 1842 is as much a part of the present as the events of yesterday. In Pushtun tradition, no guest may be left unprotected, no offence left unpunished: the result is a web of feud and counter-feud, alliances and vendettas, embedded in time and tribal memory. That is the sense of history that Britain faces in Afghanistan: not a schoolbook past of dates and great men, but something far more organic and immediate. In many parts of Afghanistan, people still refer to the British as the "English tribes". We are woven into Afghanistan's tribal past. Playing the "British not American" card is an extraordinarily risky gambit.

In 1839 subduing Afghanistan looked like a walkover, just as it did in 2001. The "war" was won with ease and modern explosives (cannon), the ousted warlord emir took to the hills and we installed a ruler more to our taste. Victoria's Government blandly announced that: "In restoring the union and prosperity of the Afghan people, British influence will be sedulously employed to further every measure of general benefit, to reconcile differences ... and put an end to the distractions by which, for so many years, the welfare and happiness of the Afghans have been impaired."

This did not happen. Under-manned, underfunded and with no clear mission, the British in Kabul blithely brought out their memsahibs, staged tea dances and played polo. Their military intelligence was hopeless. Outside Kabul, resentment and resistance built steadily, despite large disbursements of cash to tribal chiefs.

Four months before he was slaughtered with the rest of the British contingent, the government envoy in Kabul told London that the situation was "perfectly wonderful". That remark has an uncomfortable echo of John Reid's prediction, as Defence Secretary last year, that Britain could subdue the southern areas "without a shot fired". Then, as now, the enemy could be identified only vaguely: a mixture of fanatics, tribesmen, bandits and mercenaries, united only by the desire to kill those in British uniforms.

Some of the same mistakes are being played out today. A force of 3,300, with only six Apaches and six Chinooks, seems wholly inadequate for the task of controlling an area four times the size of Wales. That task is itself not easy to discern: to subdue, to root out the Taleban, to stop poppy cultivation, but at the same time to win hearts and minds, to pacify, to make friends. One billion pounds in aid has been spent in Afghanistan but, as ever, an uncounted proportion has ended up in the pockets of the warlords, while the drug trade thrives.

British commanders seem genuinely surprised by the level of resistance they are facing in Helmand. The Ministry of Defence described the Taleban attacks as "unexpected". Unexpected? This is a country that has been battling foreign forces and their new-fangled weapons, almost as a way of life, ever since Alexander the Great arrived with his elephants. The Soviets were still being "surprised" by the level of Afghan resistance when they finally pulled out in 1989, leaving 50,000 dead and a million dead Afghans.

The British never ceased to be baffled by the arithmetic of Afghanistan, where their highly trained troops with expensive equipment struggled to contain shadowy Afghan insurgents lurking behind rocks and armed only with cheap muskets (jezails). Rudyard Kipling caught the British incredulity perfectly:

A scrimmage in a border station -

A canter down some dark defile -

Two thousand pounds of education

Drops to a ten-rupee jezail -

Afghanistan desperately desires and deserves peace, but even with more men, more arms, and a clear policy, Britain may not be able to impose it. For the Afghans have a grim, semi-secret weapon: a wounded history, in which Britain played a central part that we have all but forgotten, and they have not. Link

Ben Macintyre is the author of Josiah the Great: The True Story of the Man Who Would Be King

<< Home