Comedy

Excerpt:

"We stand with the mothers and fathers in every culture who want to see their children grow up in a caring and peaceful world." Link

They just got a different tool to use than we do: They kill innocent lives to achieve objectives. That's what they do. And they're good. They get on the TV screens and they get people to ask questions about, well, you know, this, that or the other. I mean, they're able to kind of say to people: Don't come and bother us, because we will kill you. Bush - Joint News Conference with Blair - 28 July '06

[...] in Lebanon they design attacks and manipulate the media to try to demoralize public opinion. They doctor photographs of casualties, use civilians as human shields and then provoke an outcry when civilians are accidentally killed in their midst, which of course was their intent - Rumsfeld August 29, 2006

[...] in Lebanon they design attacks and manipulate the media to try to demoralize public opinion. They doctor photographs of casualties, use civilians as human shields and then provoke an outcry when civilians are accidentally killed in their midst, which of course was their intent - Rumsfeld August 29, 2006 One Israeli accident [air strike] hit a farm near Qaa, close to the Syrian border in the Bekaa Valley where human shields [workers], mostly Syrian Kurds, were loading plums and peaches on to trucks. 33 were killed and 20 wounded. "Outcry" was limited.

One Israeli accident [air strike] hit a farm near Qaa, close to the Syrian border in the Bekaa Valley where human shields [workers], mostly Syrian Kurds, were loading plums and peaches on to trucks. 33 were killed and 20 wounded. "Outcry" was limited.

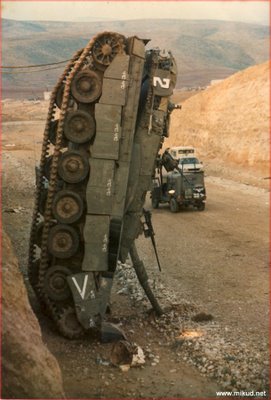

"For the last six years we were engaged in stupid policing missions in the West Bank," he said. "Checkpoints, hunting stone-throwing Palestinian children, that kind of stuff. The result was that we were not ready to confront real fighters like Hezbollah." Link

"For the last six years we were engaged in stupid policing missions in the West Bank," he said. "Checkpoints, hunting stone-throwing Palestinian children, that kind of stuff. The result was that we were not ready to confront real fighters like Hezbollah." Link

Objective reporting of the fighting in Helmand is lacking due to the refusal of commanders to have journalists at forward bases.

Objective reporting of the fighting in Helmand is lacking due to the refusal of commanders to have journalists at forward bases. The pair were wearing leather jackets and thick jumpers, speaking what was believed to be Arabic and repeatedly checking their watches.

The pair were wearing leather jackets and thick jumpers, speaking what was believed to be Arabic and repeatedly checking their watches. Ten coffins draped with Hezbollah flags of fighters, who died in south Lebanon during the offensive with Israel, are carried aloft by their comrades during a mass funeral procession in the Bouj El Barajneh suburb of Beirut, Lebanon, Saturday, Aug. 19, 2006. (AP Photo/Kevork Djansezian)

Ten coffins draped with Hezbollah flags of fighters, who died in south Lebanon during the offensive with Israel, are carried aloft by their comrades during a mass funeral procession in the Bouj El Barajneh suburb of Beirut, Lebanon, Saturday, Aug. 19, 2006. (AP Photo/Kevork Djansezian)

During a congressional hearing on 17 May administration officials stressed that Egypt's current regime had backed US interventions in the region, and had generally supported Washington's pro-Israeli foreign policy and US economic ambitions in the Middle East.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of State of the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs Michael Coulter stressed the pivotal role of the Egyptian government in US military plans in the region. He described US military aid to Egypt -- a hefty $1.3 billion in foreign military financing (FMF) and $1.2 billion in international military education and training (IMET) -- as an instrument intended to "create a defence force capable of supporting US security".

"Military assistance is critical to the development of a strategic partnership with Egypt, and has contributed to a broad range of US objectives in the region," Coulter said. "Cooperation is increasing each year, and is often difficult to quantify in one single observation." Link

[...] More than 1,000 British Muslims have been arrested under anti-terrorist legislation, but only 12% have been charged. That is harassment on an appalling scale. Of those charged, 80% were acquitted. Most of the few convictions - just over 2% of arrests - are nothing to do with terrorism, but some minor offence the police happened upon while trawling through the lives they have wrecked.

* The prisoners, who served as casus belli (or pretext) for the war, have not been released. They will come back only as a result of an exchange of prisoners, exactly as Hassan Nasrallah proposed before the war.This will not replace Hizbullah. Hizbullah will remain in the area, in every village and town. The Israeli army has not succeeded in removing it from one single village. That was simply impossible without permanently removing the population to which it belongs.

* Hizbullah has remained as it was. It has not been destroyed, nor disarmed, nor even removed from where it was. Its fighters have proved themselves in battle and have even garnered compliments from Israeli soldiers. Its command and communication stucture has continued to function to the end. Its TV station is still broadcasting.

* Hassan Nasrallah is alive and kicking. Persistent attempts to kill him failed. His prestige is sky-high. Everywhere in the Arab world, from Morocco to Iraq, songs are being composed in his honor and his picture adorns the walls.

* The Lebanese army will be deployed along the border, side by side with a large international force. That is the only material change that has been achieved.